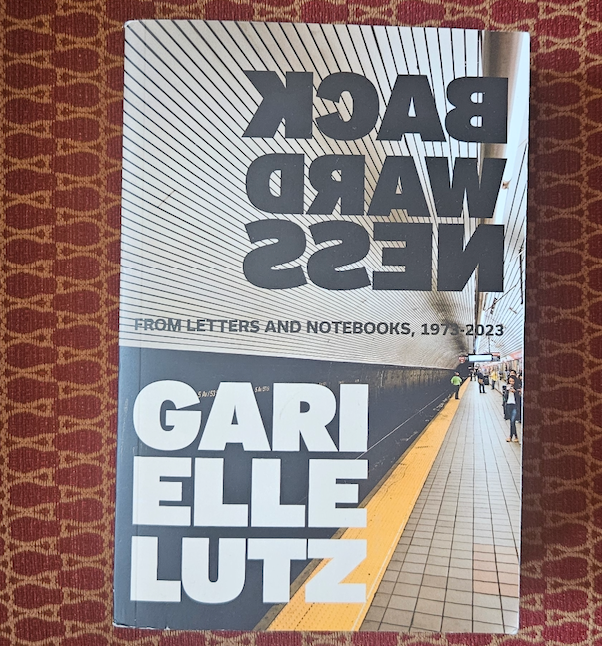

On a Sentence in Garielle Lutz’s Backwardness

“We ducked into a restroom at Burger King to kiss quickly, shiftily, before somebody barged in to take a simple, easy-hearted, shank-of-the-evening workingman’s shit.” p.8

Is there one typical Garielle Lutz sentence? Or can there be one that stands for her oeuvre in general? Probably not, but I’ve come upon one that works in certain ways to typify the structure, harmony, and feelings in that strange, unwonderful, but funny universe, wherein one takes the fruitfulness of life and suddenly squashes it, like the mite it can sometimes turn out to be. In her work, hopes are constantly built up and then dashed, joys dissolved, while the Americana of Pennsylvania and its environs keeps humming about, pressing on, and pressing us into differing contortions to find some way out of the worst. Indeed Edgar’s edict in King Lear is the perfect catchphrase for a body of work in which the word “worst” plays an oversize role in two of her books: Stories in the Worst Way and Worsted — “And worse I may be yet: the worst is not so long as we can say, ‘This is the worst.’”

Lutz’s above sentence comes near the beginning of her 932-page most recent book, written to “leave behind some kind of account.” It’s in the midst of a recollection of first love, but the journey is spangled. Lutz’s vaunted interest in Americana sets the stage, as she speaks of Woolworth, just before “The Home of the Whopper” comes up. The sentence itself — twenty-four words extruded one from the other — is a marvel of sonics: “kiss quickly, shiftily”; “before somebody barged”; and the uncanny “a simple, easy-hearted, shank-of-the-evening workingman’s shit.” Before anything else there is Lutz’s rhythm and coloring, via consecution, as Gordon Lish told his students to constantly look back to guide one in what to put next. But the sentence is also extremely funny. We begin with youth — young college kids in love — but suddenly that lyrical, romantic, and naive world is torn down by the ugly adult world of “must-dos,” barging in and taking a shit. Yet this is not just any regular bowel movement.“Easy-hearted” stands in relation to the friction of young love (they are having issues) but the action the man takes is also a specter for the rest of their lives which will be filled with responsibilities they could not imagine. Though they kiss “shiftily,” these two lovers are light-hearted, but their moment is undercut and ends in defection, in the sore reality of the body’s intake and outtake. Kissing and shitting have never such close bad bedfellows (the next sentence ingrains this: “We washed our hands exaggeratedly at the twin sinks.”) Lutz, whether consciously or unconsciously is drawing a true, scientific, and hilarious contrast between these two ends of life, both captivating and captive. Et in Arcadia Ego. The body will always toll, whether in sickness or in health. Recall being in love in public and seeing other people that have to pick up the trash or make your order at a diner. You are on top of the world, but there are reminders of the realities that lurk — nothing can last forever, and, eventually, someone has to go to work. Now let’s look closer at those nearly concluding words of the sentence before the deliverance of the action that is also the remainder: “easy-hearted,” “shank-of-the-evening,” and “workingman’s.” “Easy-hearted” — a Baroque-era term from John Milton. “Shank-of-the-evening” — OED: “the latter end or part of anything: the remainder or last part of a thing.” This American term first appears in 1828. It was initially used to refer to twilight — and this concurs with the end of a work shift — nine to five in winter. Plus, “shank,” of course, means part of a leg and leg can sometimes be synonymous with the other male appendage in front. “Workingman’s”: Again from the Baroque-era. And one can easily slide into all the compounds, like “workingman’s lunch,” or: “college,” “association,” “institute.” Why are these three words used? They signify a type of living that will eventually come to envelop the two young lovers, but the spotlight rhythm of presentation embeds them, as caesuras separate each startling, unique word. No one has ever used those three words in a sentence in all the annals of writing in English, with the only close examples being language deployed in the 1880’s — the high point of the Second Industrial Revolution and The Gilded Age in the U.S, which transformed the social classes both for the good and the bad. Lutz has keyed into our country’s past by making its present — the land of strip-malls, dollar-stores, and fast-food and imitation-food restaurants — into the plastic and watercolor settings where we go to relieve our hungers and look at people in our socio-economic group, places full of much mischief, surreality, irreality, and a host of crackpots.

Years ago, I read “Metaphysical Light in Turin,” an essay in Guy Davenport’s Objects on a Table. After beginning with Nietzsche, he goes into the notion of “still life” demonstrated in the poems of John Keats, particularly “The Eve of St. Agnes,” which has “the theme of making off with a bride by a lover [Porphyro] unacceptable to her clan.” In the Keats excerpt the lover goes to the woman’s [Madeline] bedroom and makes a still life of fruit by her bed: “Of candied apple, quince, and plum, and gourd;/With jellies soother than the creamy curd…” Davenport then writes that “A happy, Joycean tangle of etymologies mak[ing] serendipitous puns” is on display, and “Porphyro (purple) is an apple color, and a Madeline is a kind of pear. Apple topples us from grace; pear, symbol of incarnation, saved us.” Then comes the key paragraph:

And when the skeptical student in the back of the room asks if Keats knew this, and intended it, we must say no, but that language knew it for him, and carried the meaning as genes pass on information from organism to organism. Keats knew herbals, as a poet and pharmacist; he knew Milton, Spencer, and the Bible. He used words as an artist uses colors, with harmony taking precedence over local accuracy.

“Language knew it for him.” And when the 2024 student asks, Did Lutz put all these possibilities into the sentence? We should say her harmony, humor, and rhythm knew it for her. The shit is not enough to be described as “workingman’s” or “shank-of-evening” — it has four adjectives: beginning with the most common “simple,” before proceeding to the most romantic “easy-hearted,” before the most rare and loaded “shank-of-the-evening,” before, finally, the most solid and brawny. The syllable counts go: one, two, four, six, four, one, building an Alp of syllabication.

Lutz knows words, grammar, usage, and punctuation like few people on this planet. Her syntax is like the timing of a great stand-up comedian. But without Lutz knowing “shank-of-the-evening” meant “twilight,” and perhaps primarily choosing it for harmony-sake, the language knew it for her, as she has been tracking the day to day lives of the workers making up Americana for her whole writing life. Lutz might be unconsciously saying the four ancient humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm — and their influence on the body and its emotions) are destined never to be balanced in the modern U.S. but this disjunction lets in the humor that helps people get through the day better than anything.